More trade from a land down under

Last week’s announcement of a trade agreement with Australia (along with a soon-to-be-finalised deal with New Zealand) is good news for the Government’s post-Brexit trade strategy. The deal with Australia represents the first substantively new deal, providing evidence of the opportunities the UK now has after leaving the EU. But both deals are small in economic terms, and so are unlikely to shift UK trade or sectoral specialism in a major way. Indeed, the long-term impact of the deal with Australia is estimated to be a boost to UK GDP of just under 0.1 per cent. And, although small gains are spread across a number of sectors, the losers from these deals are much more concentrated in parts of the agricultural sector. These sectors are likely to experience notable declines in output and employment, with job losses likely to be concentrated in rural regions and among lower-skilled employees.

Looking beyond the small (and long-run) economic impact, these agreements have greater strategic importance. This is partly because they will act as a template for future deals. In this context, a concern is the lack of commitments on net zero despite Australia’s poor record on environmental issues. This suggests that the Government is unlikely to prioritise climate objectives in future negotiations. But these deals are also significant because they will act as stepping stones in the plans to deliver an Indo-Pacific ‘tilt’ to UK trade policy. The impact of this broader strategy is something that we will return to in future work.

New trade agreements with Australia and New Zealand

The new free trade agreements (FTAs) with Australia and New Zealand are symbolically and politically important for the UK Government. Although the UK has been successful in ‘rolling over’ the majority of agreements that the EU had with other countries, the newly-announced deal with Australia is the first FTA to be negotiated from ‘scratch’ since leaving the EU. It will make Australia the first country the UK has preferential access to compared to EU countries.

The overall economic importance of the deal is small but not insignificant. UK exports to Australia in 2020 were of a similar order of magnitude to exports to Sweden, at around 1.7 per cent of total UK exports. Government estimates suggest the economic value of the agreement is estimated to increase GDP by just 0.08 per cent in the long run.

The UK-New Zealand FTA, which reached ‘agreement in principle’ in October, will soon follow suit. It will be even smaller economically and hold less political importance, but, combined with the agreement with Australia, represent an important step to joining the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (or CPTPP) – a group of trade agreements between 11 countries, mainly in the Pacific region.

The winners and losers from the new FTAs

Despite the difference in scale, the Australia and New Zealand agreements are similar in the expected economic impacts they are likely to have. Government analysis of both agreements suggests exports to these countries are likely to increase. The newly announced deal with Australia is expected to increase UK exports to Australia by 14 per cent; and the deal with New Zealand could increase exports by between 3 and 8 per cent.

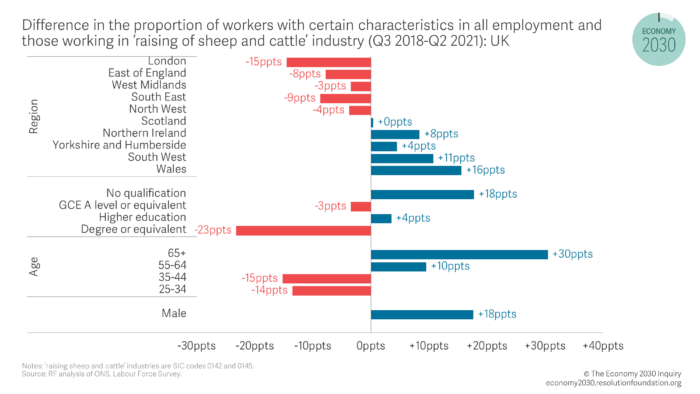

Figure 1 : Sheep and cattle farming employment is concentrated in rural regions and among older, lower skilled and male workers

Small gains are expected for a number of sectors, but losses are expected to be concentrated in ‘semi-processed foods’. This loss is driven by the anticipated increased imports of beef and lamb following eventual liberalisation of tariffs. The UK currently imports 81 per cent of its sheep meat, 53 per cent of its wool and 2 per cent of its fresh bovine from Australia and New Zealand, despite their overall share of UK imports being just over 1 per cent. Australia and New Zealand are both highly competitive producers in these products with higher revealed comparative advantage. Meanwhile in the UK, grazing livestock farms have the lowest incomes of all UK farm types.

The sheep- and beef-producing sectors in the UK are fairly small, representing just 0.1 per cent of UK employment in 2021. But any job losses would be concentrated in rural regions such as Wales, the South East, Yorkshire and Northern Ireland. And, as shown in Figure 1, the labour force in these sectors is disproportionately male (70 per cent compared to 53 per cent for all employment), older and less well-educated. That said, any eventual job losses would materialise over several years, however, as liberalisation is phased in.

It is notable the UK is going beyond where the EU typically has in liberalising agricultural tariffs; this could reflect that the UK is no longer constrained by the larger agricultural producers in the EU, but could also demonstrate that the UK has less power than the EU when negotiating trade deals. Either way, the Government appears to be showing a willingness to accept some losses in less-productive and competitive domestic industries, even in highly politically sensitive industries such as agriculture, in order to deliver its Global Britain agenda.

The broader significance of agreements with Australia and New Zealand

As set out in our previous work, a country’s trading relationships are closely related to its overall economic strategy, not least because they affect the incentives for goods to be produced domestically rather than imported. Although the size of trade with Australia and New Zealand is too small to have a major bearing on the overall shape of the economy, these deals provide some clues as to the Government’s overall approach.

Beyond its political importance, this trade agreement will also set a precedent for future deals. Trading partners entering negotiations with the UK will naturally seek to replicate the provisions and market access agreed in the Australia FTA, the UK’s first independently negotiated agreement. In particular, current or potential negotiation partners, such as India and the US, will presumably be noting how much further this agreement goes than existing EU agreements, notably on liberalisation of agricultural tariffs. But it also sets the tone for future agreements on non-trade commitments such as on the environment.

In this context, a worry is that the deal with Australia does not help the UK’s drive to be a world leader in achieving net zero. Here, Australia is seen as a laggard among rich countries: in the run up to the COP26 summit, the Australian Government committed to reaching carbon neutrality by 2050, but made it clear that its reliance on fossil fuels would continue for the foreseeable future. And, unlike the negotiating objectives for the deal with New Zealand, the FTA with Australia contains no reference to measures to achieve net zero. All this sets a worrying precedent for the extent to which the Government is likely to prioritise climate objectives in future trade negotiations.

Arguably even more significant is what these deals tell us about the future direction of trade policy. These agreements are an important step towards accession to the CPTPP, as Australia and New Zealand are two of the four members with which the UK does not have an existing deal. Joining the CPTPP is part of the UK’s Indo-Pacific ‘tilt’ outlined in the Integrated Review. We will return to the economic implications of this strategy in future work.