Britain has been so buffeted around by economic crisis over recent years that it feels almost indulgent to cast beyond the ongoing emergency phase of economic policy to consider the longer-term prospects and pre-requisites for shared growth. But, as current US experience shows, growth is certainly possible and purposeful governments can combine short and longer-term agendas.

So, let’s look beyond 2023’s gloom to ask what it would take for a period of growth to raise the living standards of the whole of society? The glass half-empty answer is: an awful lot. The half-full response would say: true, but it only requires feats we have managed to pull off in the not too distant past.

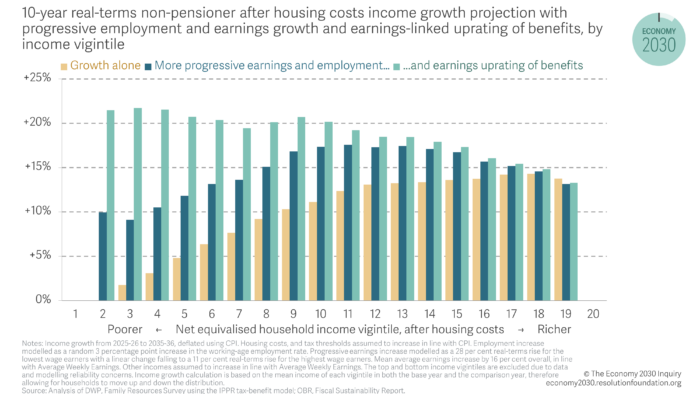

A new report from the Resolution Foundation by Mike Brewer, Karl Handscomb, Cara Pacitti and Lalitha Try helps crystallise the shared growth challenge. It models a number of scenarios to examine the impact on household incomes across the distribution. It starts by assuming a return to reasonable, not stellar, real wage growth (in line with the OBR’s current outlook). Next it says, ok, what if that wage growth is skewed towards those on low-wages (which we have seen in a number of times since the minimum wage was introduced, not least since the introduction of the National Living Wage). Then it layers on top of this an increase in the employment rate of the scale that occurred during the 2010s (no mean feat then, harder to repeat now).

The chart below shows how these different ‘what ifs’ combine to generate significant gains in living standards for much of the population. What it also demonstrates is that, even in this happy state of affairs, these gains are still skewed toward the middle and upper-middle part of the distribution and the gap with the bottom grows. This brings home, in case it wasn’t obvious, that achieving fully shared growth means running up a steep hill.

To ensure a bottom-heavy pattern of income growth the essential additional condition is that social security entitlements rise in line with earnings rather than prices (or more specifically, the higher of the two). Over the longer-term the stance on benefit uprating matters for two key reasons. First, large swathes of the country will continue to rely on benefit income – the poorest fifth of working-age Britain receive roughly half their income from work (compared to 94 per cent for the richest fifth). This group, which changes over time, includes a large share of households with someone with a disability, as well as low income families with children. If we fail to increase benefits as GDP rises then these households inevitably fall further behind.

Second, and crucially, steady growth is itself very likely to continue to push up housing costs roughly in line with typical incomes (as it has done over the last two decades). Again, uprating in line with inflation is likely to mean that households who are reliant on benefits to cover market rents will tend to become worse off over time.

An obvious, and often made, response to all this is that increasing benefits is a self-defeating strategy as it inevitably erodes the incentive to work. But uprating benefits in line with earnings simply preserves the strength of current work incentives. Indeed, given that any strategy for shared growth would involve the minimum wage rising at least as fast as average earnings, the incentives to work for those in low-paid work should still rise even with benefits indexed to average earnings.

We can also look to other advanced economies for insight on how benefit generosity intersects with labour market performance. Earnings-uprating does indeed happen in a number of successful economies. New Zealand has recently adopted this approach and Germany, Belgium, and the Netherlands all uprate their equivalent to the UK’s means-tested benefits with reference to a combination of changes in earnings, GDP and prices.

But to get a broader sense of how a different strategy on benefit-generosity could interact with a flexible labour market, like the UK’s, we have a readymade case study: Danish ‘flexicurity’. This is the clunky label first given in the 1990s to capture Denmark’s unique approach to combining flexibility in the jobs market with high levels of income security. For a decade it received burgeoning international attention, but this has declined since 2008 as austerity and crisis management dominated economic and social policy discourse. Another new report for the Resolution Foundation by Anna Ilsøe and Trine Pernille Larsen updates our understanding of how this system has performed and asks what lessons it might offer the UK in the 2020s.

The authors point out both striking similarities and differences between the two nations. When it comes to key metrics like unemployment, the employment rate and job mobility there is little between them. Similarly, if we look at key measures of flexibility – like ease of hiring and firing – both appear near the top of the OECD league table.

But when we turn to economic security the similarities end. Take benefit generosity: Danish unemployment insurance is set at a high rate – offering up to 90 percent of prior earnings for up to two years, with a cap of just under €2600 a month which results in a typical replacement rate of 57 percent (far higher than the UK’s 35 percent). Danish unemployment insurance covers around four out of five workers but even those not eligible can fall back on lower but still generous means-tested social assistance. The basic monthly level of means-tested support for claimants with one child are almost three times higher in Denmark (€2,300) than in the UK (£742 or €850).

High levels of flexibility, and far greater income-security, come together via a third, vital, component of flexicurity: intensive support to help the unemployed find work and move roles. Denmark spends more on active labour market (ALM) policy than any country in the OECD – around 1.2 per cent of GDP, four times more than the UK. Personalised support comes in the form of case workers and there is a duty on the unemployed to undertake job-search and participate in support programmes. Since the late-1990s, for example, more than half of the unemployed participated annually in an ALM programme of some sort. Training is an integrated and valued part of the system with financial support to facilitate participation. The ALM strategy is refined and evaluated – not least via regular use of Randomised Control Trials. The system costs serious money and is treated seriously by national government, employers and unions.

There is, of course, a very different context for Danish social protection. Trade unions are radically more pervasive (two out of three workers are members) and the tax-share stands at 46 percent of GDP. Nor should we romanticise it: for all its virtues it has vices too – for instance, the employment rate is almost 30% percentage points lower among non-natives compared to native Danes (a significantly larger gap than the OECD average) and, like the UK, it struggles with how best to incorporate the self-employed. And, of course, we can’t just transplant attractive elements of another system piecemeal from one nation to another.

Yet none of this should inhibit us from renewing our curiosity to learn from a near-by, open economy that has adjusted relatively successfully to globalisation and automation. Few nations have done better when it comes to securing popular consent for a national ambition to bear down on low pay and inequality, tackle job insecurity and invest in human capital.

Taken together these two reports help clarify the nature of the challenge ahead. The resumption of real wage growth (driven by productivity gains) is the most fundamental pre-condition for shared growth. A higher employment rate does significant additional work in boosting incomes near the bottom of the distribution. Achieving either of these goals would require concerted policy effort within the context of a serious economic strategy. But if we want to avoid the working-age poor being left behind then these two pillars – sooner or later – need to be bolstered by a third: benefits rising with a growing economy. This was effectively achieved in the late 1990s and early 2000s via the creation and expansion of working-age tax credits. And when it comes to pensioners there has been a solid consensus on doing exactly this (and more besides) since the mid-2000s. Achieving shared growth for everyone means forging a similar resolve to create a decent social minimum for the working age population and ensuring it rises over time with national prosperity.

All this would raise concerns about long term costs though, as the Resolution report shows, these are smaller than many would expect in part because of demographics (and half of the long-term cost could be covered by moving pensions uprating from a triple to a double-lock). And to be fully effective a new social security strategy would need to be married with a higher-road jobs market model which, among other things, raises the quality of lower-wage work and in doing so draws more people into the labour market.

We would be better placed to pull this off if we lift our gaze to consider the experience of other nations who have struck a better balance between flexibility and security; as well as mining insights from our own efforts in the past. Our current policy discourse feels small and reactive at a time when it is clear that other nations, big and small, are making strategic choices about the type of market economy they want to have. When Britain finally emerges out of its crisis-era mindset it needs to ask its own larger questions. One of these should be what our own distinctive version of flexicurity should look like for the late 2020s and beyond.

The path back to shared growth runs through British flexicurity